Paul Rogers

27 November 2015

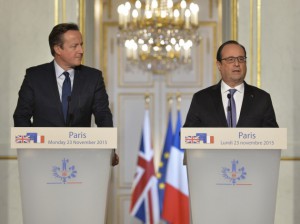

Prime Minister David Cameron with President Francois Hollande at the Elysée Palace in Paris, 23 November 2015

Summary

In making his case for extending British military operations to Syria in the House of Commons on 26 November, Prime Minister David Cameron three times stated his determination to “learn the lessons” of the last Iraq war. In the face of the urge to respond decisively to the Paris attacks, there is little evidence that sensible conclusions have been reached or that the psychology and strategy of the Islamic State (IS) have been understood. This briefing is an initial assessment of the issues raised by the vote that is likely to be held in the Commons on British involvement in Syria.

Introduction

Over the past fourteen years, ORG has published a series of analyses on potential or evolving conflicts and has acquired a reputation for accuracy in predicting outcomes. In September 2001, in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, ORG warned of the potential for long-lasting war if the primary response to the 9/11 attacks was military. Its assessment of the outcome of a war with Iraq, Iraq: Consequences of a War, published six months before that war started in March 2003, predicted that it would:

• Result in the deaths of many thousands of innocent Iraqi civilians.

• Lead to substantial regional instability, and increased support for al-Qaida.

• Draw US troops into urban warfare in Baghdad.

The report concluded that destroying the Iraqi regime by force was a highly dangerous venture and that alternative policies should be urgently developed.

This briefing examines how the Sunni resistance to the 2003-2011 occupation of Iraq eclipsed al-Qaida and changed the nature and strategy of extreme Islamist violence. It also analyses the impact of the post-2014 US-led air campaign against IS, the apparent change in IS tactics, and how the greater involvement of the UK and other actors may play into IS’s plan and trap.

From al-Qaida to ISIS

Al-Qaida evolved throughout the 1990s. By the end of the decade it had become a small but potent transnational revolutionary movement rooted in a perverse, unrepresentative version of one of the world’s main monotheistic faiths – Islam, one of the three “religions of the book” alongside Judaism and Christianity.

Its ambitious aim was to cause the overthrow of the “near enemy” regimes in the Middle East and southwest Asia, replacing them with “proper” Islamist regimes; to see Zionism destroyed; and to so damage the “far enemy” of the United States and its western partners that a new caliphate would grow outwards from the centre of Islam.

At the heart of its doctrine was an eschatological worldview whose timescales were potentially eternal. Even so, one of its key early tactics was quite specific and immediate – violent actions within the “near” and “far” enemies that would provoke massive overreactions and then sow dissension and chaos. 9/11 was the most substantial of these. The attack directly aimed at drawing the United States into occupying Afghanistan; instead, the US response was focused on using Northern Alliance paramilitaries as surrogate troops, and it took several years before the Taliban could return in strength.

Many of the violent assaults of the early 2000s – Karachi, Bali, Casablanca, Istanbul, Madrid, Jakarta, Sinai, London, Amman and many others – were undertaken by groups loosely connected with al-Qaida yet often willing to act under its banner. By 2006, however, what remained of “al-Qaida central” had limited power, and over the following six years was superseded by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

ISIS’s territorial strategy and the western response

ISIS’s new version kept the long-term aim of creating a worldwide caliphate. But from 2011, circumstances in Syria (after the start of the Arab awakening) and Iraq (after the American withdrawal) allowed for the rapid creation of an actual proto-caliphate. ISIS was therefore much more focused on territory, and won considerable success in the effort. This eventually resulted in a US-led coalition mounting a strong reaction in the shape of the air-war that started in August 2014: Operation Inherent Resolve.

The intensity of the war has been scarcely reported. It has involved 57,000 sorties and 8,300 airstrikes in Iraq and Syria that as of 13 November 2015, hit 16,075 separate targets. The overwhelming majority of the sorties were flown by US Air Force (USAF) and US Navy planes. The Pentagon estimates that 20,000 ISIS supporters have been killed. Furthermore, the withdrawal of Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates from airstrikes in Syria, mainly since these states became involved in a new war in Yemen in March 2015, means that this is now essentially a western war on ISIS’ self-proclaimed Islamic State.

Such a concentrated war would create the expectation of IS being on its knees. Yet the Pentagon also estimates that the number of active IS paramilitaries is unchanged from 2014 at 20,000-30,000, while US intelligence agencies say that 30,000 people from 100 countries have joined IS (compared to 15,000 people from eighty countries by mid-2014). The air-war, in short, is not defeating IS.

IS switches tactics

Moreover, a significant change in IS tactics has occurred. It now combines holding territory with operating overseas in a manner reminiscent of al-Qaida’s approach of a decade ago. In the past year IS has sought to make stronger connections with Islamist paramilitaries in several countries – including Libya, Nigeria (Boko Haram), southern Russia, Yemen and Afghanistan – and to bring them under its own banner. It is also promoting direct attacks elsewhere: among them two attacks in Tunisia (Tunis’s Bardo museum and Sousse’s beach resort), the destruction of a Russian tourist jet over Sinai, and bombings in Beirut and Paris.

There are almost certain to be more, not least as IS is reported to have established an organised wing of the movement with this specific aim. The plan has three purposes:

• to demonstrate power and capability, including to supplant what remains of the support for al-Qaida;

• to incite as much Islamphobia and community conflict as possible, especially in France and Britain;

• to provoke an even more intense war from the west, ideally involving western ground-troops.

All this is relevant to the decision by David Cameron to seek approval for the Royal Air Force (RAF) to join in the bombing of Syria. It is highly likely that this will be supported by the House of Commons within the next week, unless individual members can rise above the understandable desire that “something must be done”. But it is significant that behind the rhetoric about destroying and defeating IS, the government’s intention in terms of the direct assault is actually far more modest.

When parliament’s foreign-affairs committee asked Cameron what the overall objective of the military campaign was and whether it was intended to be “war-winning”, he replied: “The objective of our counter-ISIL campaign is to degrade ISIL’s capabilities so that it no longer presents a significant terrorist threat to the UK or an existential threat to Syria, Iraq or other states.” This falls far short of a military victory and no timetable is given even for this limited aim.

Back to the future

The decision to expand the war against IS is worth putting in historical perspective. By the end of 2001, three months after 9/11, the US coalition appeared to have destroyed the Taliban and massively damaged al-Qaida. This enabled George W Bush to declare success in his state-of-the-union address in January 2002. Yet al-Qaida went on to facilitate attacks worldwide, and the war against a resurgent Taliban continues to this day.

By May 2003, President Bush could declare “mission accomplished” against Saddam Hussein’s regime after just six weeks, but an immensely costly eight-year war ensued. In 2011, President Obama felt Iraq sufficiently secure to withdraw all US combat-troops, but within two years ISIS was rampant. That same year, France and Britain celebrated the end of the Gaddafi regime in Libya only for the country to disintegrate into a violent, failing state and weapons to proliferate across the Sahel.

What is frankly amazing is that the same mistakes are being made, and that western leaders are falling into the same traps. There is no recognition at all that IS is intent on provoking an expanded war, that this is what it is going to get, and that its leadership will be well satisfied with its achievements.

Paul Rogers is Global Security Consultant to Oxford Research Group (ORG) and Professor of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford. His Monthly Briefings are available from their website, where visitors can sign up to receive them via their newsletter each month.

These briefings are circulated free of charge for non-profit use, but please consider making a donation to ORG, if you are able to do so.

A version of this briefing was published by openDemocracy on 27 November 2015