Paul Rogers

1 March 2017

Summary

The recent statement from the UK’s new Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation that the terrorist threat to the country is at its highest level since the 1970s raises at least three crucial questions that this briefing seeks to answer. Why is the apparent threat so high, and apparently rising, after 15 years of high-intensity ‘war’ against international terrorist groups? Why is the specific threat from Islamic State (IS) so substantial at present? Finally, and most overlooked, why is there such a disconnect between the intense war in Iraq and Syria and the perception of threat in the UK? As the Trump administration prepares a new, escalated strategy against IS, these questions matter more than ever for Trump’s closest allies.

Introduction

In the UK, the position of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation (IRTL) dates back to parliamentary concern over new legislation in the 1970s in response to the rapid increase in violence in Northern Ireland. A number of reviews from 1978 to 1984 were followed by regular annual reviews and eventually a more permanent role evolved, with the reviewer being appointed for a three-year term which is renewable. In a further development some of the functions were given a statutory basis in the 2005 Prevention of Terrorism Act,

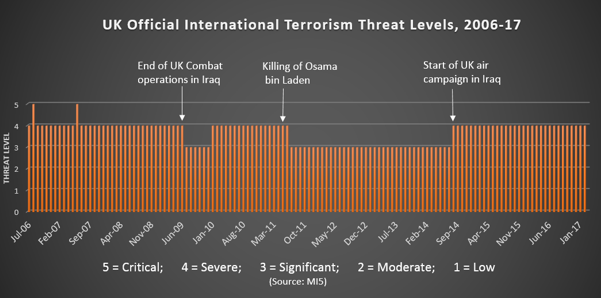

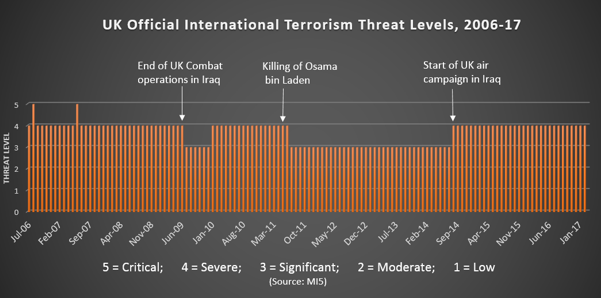

The incoming Independent Reviewer, Max Hill QC, is an experienced prosecuting counsel who has been involved in a number of terrorism prosecutions. Within days of his appointment on 21 February he gave his assessment of the threat to the UK, principally from Islamic State (IS) supporters, in an interview with the Sunday Telegraph, expressing the opinion that the threat was its at highest level since the 1970s. The official threat level was last at the highest point (‘Critical’) for a few days in 2007, so Anderson is expressing this view more as a general trend rather than a sudden change which, in a way, means that it deserves particular attention.

This opinion from a highly experienced and knowledgeable figure immediately raises the question of why this should be. At the very least it suggests that more than fifteen years of sustained western military actions against extreme Islamist paramilitary organisations have not been successful, but there is also the question of why there should be a specific threat from IS and why it should be so substantial at the present time. This briefing places the current situation in a longer term context and also questions whether the low profile nature of the intense US-led air war makes it less easy to have open discussions in the UK about the nature and implications of the fifteen years of failure of military action and the reasons for the current enhanced threat level.

This opinion from a highly experienced and knowledgeable figure immediately raises the question of why this should be. At the very least it suggests that more than fifteen years of sustained western military actions against extreme Islamist paramilitary organisations have not been successful, but there is also the question of why there should be a specific threat from IS and why it should be so substantial at the present time. This briefing places the current situation in a longer term context and also questions whether the low profile nature of the intense US-led air war makes it less easy to have open discussions in the UK about the nature and implications of the fifteen years of failure of military action and the reasons for the current enhanced threat level.

Al-Qaida and the Far Enemy

In the wake of the catastrophic 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington, the United States and a small coalition of mostly western states succeeded in terminating the Taliban regime in Afghanistan and dispersing the al-Qaida movement. The move was broadly popular in western countries but the subsequent decision of the Bush administration to extend the war against al-Qaida into a broader war against an “axis of evil” of rogue states was less widely accepted, especially after the termination of the Saddam Hussein regime and the occupation of Iraq.

During this period in 2002-03 the al-Qaida movement survived and also encouraged attacks on the “far enemy” of the United States and its closest allies. In some cases the encouragement was not specific but in others there was more direct involvement in the planning and execution of attacks, but all in their different ways were seen as promoting al-Qaida’s long-term aim of creating an Islamist caliphate. Between 2002 and 2006 they included attacks, frequently on western targets, in Istanbul, Casablanca, Sinai, Amman, Djerba (Tunisia), Jakarta, Bali, Islamabad, Mumbai, Mombasa, Madrid and London. Then, during the mid-2000s, the focus was more on attacks, often targeting Shi’a Muslims, in Pakistan and especially Iraq, where al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) was intensely active. By 2011, when Osama bin Laden was finally located and killed in Pakistan, al-Qaida had become much more limited as a transnational movement, engaging in few attacks beyond the Middle East and south-west Asia.

After 2011 and the Arab Awakening some of the groups aligned with al-Qaida succeeded in gaining support by limiting the dominant narrative of the caliphate and adjusting more to local cultures and grievances, al-Nusra Front in Syria being perhaps the best-known example. At the same time, the erstwhile AQI (ex-communicated by bin Laden in 2006) had sufficiently survived the intense US-led shadow war against it and by early 2013 had extended its operations into Syria’s civil war. Reformed as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2013, it proclaimed an actual geographical caliphate under its control in northern Syria and Iraq following its spectacular offensive of mid-2014. At its peak, this self-declared caliphate covered a population of some six million people under an often brutal yet technocratically competent regime that gained many thousands of recruits especially but not only from across the Middle East and North Africa.

IS and its Aims

Although IS and al-Qaida could both be described as transnational revolutionary movements determined to create an Islamist caliphate and both have an eschatological dimension which looks beyond earthly life, by 2014 they had come to differ in an important respect. For al-Qaida, the creation of a caliphate would best be achieved by the overthrow of existing leaders such as the house of Saud in Saudi Arabia, though this would also involve attacks on the far enemy that supported so many unacceptable states right across the Islamic world, especially in the Middle East. Attacks on the far enemy therefore formed a significant component of their actions, not least in the 2002-06 period.

In contrast, for IS the actual creation of a physical caliphate by mid-2014 was at the centre of its aims, demonstrating in a very powerful and symbolic manner what could be achieved. Thus almost the entire emphasis of the movement was on the expansion and consolidation of the caliphate, with attacks on the far enemy being of secondary significance. It follows that, if this has been the case, why is there the high level of risk to the UK at the present time?

The change on the part of IS towards overseas attacks relates to the start of the air war in August 2014. This was initiated by the United States but with a number of regional and western states joining to form a major coalition operating mainly by employing strike aircraft and drones. Although the sheer intensity of the air war only peaked in 2015, even by the end of 2014 it would have been clear to the IS leadership that it was facing a far greater and more immediate threat to its caliphate than had been anticipated.

Since then it has put far greater effort into encouraging and even facilitating attacks elsewhere, with these serving two main purposes. One is to demonstrate both to its supporters and the wider world that it is still a powerful force with international reach, but the other is that any attack involving civilian loss of life is likely to damage community cohesion in the states of the far enemy, stirring up anti-Muslim rhetoric. Such an aim is aided greatly by the many political changes now evident in the west, not least the Trump presidency with its vigorous anti-Muslim views but also Marine le Pen’s Front National in France, UKIP in the UK, Viktor Orban in Hungary, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands and many others.

Indeed it is likely that as IS faces even more intense conflict in Iraq and Syria it will present its caliphate as a symbolic gesture that may not survive the short term but will come again in the future. IS itself may go underground while seeking to stage more attacks, not least within the far enemy and confident that in doing so it can further encourage Islamophobia and thereby weaken western societies that are already stressed by many new political tensions and instabilities.

Implications: Trump and the Western Response

How western states conduct the continuing war against IS relates very largely to the posture of the new Trump administration. In his speech to both Houses of Congress on 28 February, President Trump had little to say about foreign affairs but did repeat his intention to crush IS:

“As promised, I directed the Department of Defense to develop a plan to demolish and destroy ISIS — a network of lawless savages that have slaughtered Muslims and Christians, and men, women, and children of all faiths and beliefs. We will work with our allies, including our friends and allies in the Muslim world, to extinguish this vile enemy from our planet.”

How this will be reflected in the military posture is not yet clear – he is planning a sizeable increase in military spending directed mainly at expeditionary and interventionist warfare but beyond that the precise changes are still to be announced, especially in relation to IS. There is some evidence that he has already had an impact on the intensity of the war, with a greater involvement of Special Forces in Yemen, closer involvement of the US Army in the use of forward-based artillery around Mosul and more integration of US Special Forces with Iraqi Army units in the direct urban counterinsurgency operations within the western part of the city.

At the same time there are indications of disagreements within the administration. The new National Security Advisor, Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, is cautious about any general representation of an overall “threat from Islam”, in contrast to some of Trump’s key civilian advisors, but the more significant tension may be between those who favour “more of the same”, such as intensive use of air power and Special Forces, and others who see it as necessary to have more boots on the ground.

The Secretary of Defense, General James Mattis, delivered the results of an intense 30-day study on defeating IS to the White House on 28 February and early reports indicate that serious consideration is being given to deploying regular combat units to Syria in the coming operation to take control of the key IS city of Raqqa. This is paralleled by the recent widespread exposure of the view that if IS is suppressed in Iraq, such is the extent of political instability in the country that a substantial US military presence in the country will be necessary for some years to come.

Recalling the experience of western states in Iraq since 2003 this will actually represent a substantial change from the eight years of the Obama administration and such an approach may actually be the most significant development. To put it simply, the United States will be back there for the long term and in all probability the UK government will be the most significant ally involved. That has many implications for the current Conservative government and leaves one key question remaining.

Conclusions

That question is why is there such a disconnect between the intense war in Iraq and Syria and the perception of threat in the UK. People are likely to say – why us? There is, in other words, no recognition of the relationship between the threat of terror attacks in Britain and that war, even though the UK is an integral and significant part of the war. We in the UK have been part of a thirty-month war that has killed at least 50,000 IS supporters, according to Pentagon estimates. To put it at its most crude – we have killed tens of thousands of them and they want to kill at least hundreds of us.

This should come as no surprise and yet it does, not least because the war against IS is primarily a war by remote control which hardly figures in the media. There are no longer thousands of boots on the ground and no longer are there coffins being flown back to Britain every other week. Compared to the average of 207 and 112 British service personnel killed or wounded in action every year in the Afghan (2002-14) and Iraq (2003-09) campaigns, respectively, not one member of the British armed forces has yet been a casualty of the current air war. It is a hidden war and there is therefore scarcely any debate either in parliament, the media or in the country as a whole. This lack of discussion about the merits of current UK policy in the Middle East is one of the most worrying aspects of war by remote control. It is one reason why ORG hosts the Network for Social Change’s Remote Control Project, one of the very few endeavours that works to open up what is happening to wider consideration.

Where this links with the incoming Trump administration is that as the war expands the UK’s involvement in Iraq, and most likely in Syria as well, is likely to increase, given that Theresa May’s government appears intent on being Trump’s closest ally. As the involvement increases it may well become much more visible. If so, then a public debate on the merits or otherwise of the policy is far more likely, in marked contrast to the current situation.

Image (cropped) credit: Elliot Brown/Flickr

About the Author

Paul Rogers is Global Security Consultant to Oxford Research Group and Professor of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford. His ‘Monthly Global Security Briefings’ are available from our website. His new book Irregular War: ISIS and the New Threats from the Margins will be published by I B Tauris in June 2016. These briefings are circulated free of charge for non-profit use, but please consider making a donation to ORG, if you are able to do so.

Copyright Oxford Research Group 2017.